It seems that taxes are all we talk about. They come in every form and in every aspect of our lives. We are told they are inevitable…and they are, but what about managing the money once we hand it over. James R. Coggins takes a closer look into the current federal governments handling of your tax dollars and how it affects you!

– by James R. Coggins

When most Canadians look at a federal government budget (or a provincial government budget), they look to see what is in it for them. Is there some new program or subsidy or grant that will benefit them or their children? Is the government going to provide a home ownership grant or a child daycare grant or an increase in government pensions or even a new highway to their community? They also look at taxes. Is the government going to increase (or decrease) income tax rates or sales tax rates or impose a new tax on alcohol or gasoline or something else?

But most citizens never look at the bigger picture, the overall budget and whether the government is projecting a surplus or deficit. Most citizens assume that is not their problem. That is a problem for the government or the politicians or someone else to solve.

They are wrong.

How wrong are they?

That is not easy to answer. It takes extensive digging to discover the facts. The 2019 budget presented by the federal government on March 19 is a 460-page document, but it contains very little factual data on government spending. It is a philosophical treatise full of vague generalities such as “investing in the middle class,” “building strong communities,” “building a nation of innovators,” “advancing reconciliation,” “delivering real change,” and “advancing general equality and diversity.” It says very little about what is actually being spent and on what. No company would ever get away with such inexact financial reporting. Shareholders (not to mention government regulatory agencies) would never allow it.

It takes a fair amount of diligent research into other government documents and non-government studies to ferret out the facts. (One would almost suspect the government does not want Canadians to know what is going on.)

The Bottom Line

Here are some of the facts.

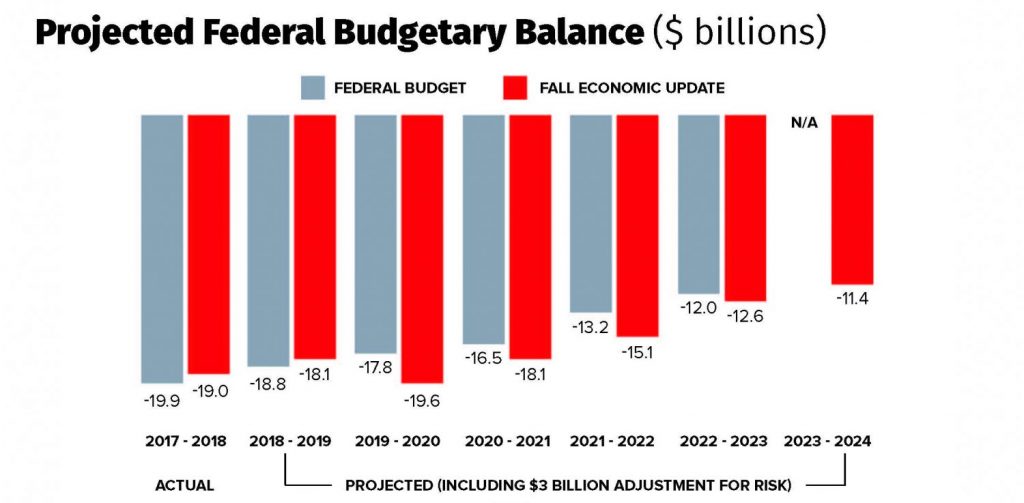

Four years ago, Justin Trudeau was elected promising to run “modest deficits” (of less than $10 billion a year) for a couple of years and then balance the budget. Those modest deficits turned out to be closer to $20 billion a year: $17.8 billion in 2016-2017, $19 billion in 2017-208, a projected $18.1 billion in 2018-2019, and a projected $19.6 billion in 2019-2020. Those add up to $74.5 billion. (The Parliamentary Budget Officer has since reported that the actual deficit for 2018-2019 was a little lower and the deficit for 2019-2020 might be a little higher.)

That $74.5 billion is on top of the $600 billion or so in deficits previous federal governments had already accumulated, but let’s ignore that for now. Let’s just look at the $74.5 billion in new debt.

Where did the government get the $74.5 billion? The answer is that it has borrowed that money from Canadians and from non-Canadians, anyone it could find willing to lend the money. Just like anyone else, when the government borrows money, it has to pay interest on that debt—and the interest payments can come from only one source, the Canadian taxpayer.

Now let us look again at that $74.5 billion. Given that there are about 37 million Canadians, this means that the increased government debt incurred by the Trudeau government alone amounts to about $2,000 for every Canadian ($74.5 billion divided by 37 million citizens).

Canada’s total accumulated debt amounts to over $18,500 for every Canadian, but let’s just talk about the debt incurred under Justin Trudeau.

The government reports that it is paying about 3.5% interest on that debt, which is a pretty favourable interest rate. In fact, it is a historically low interest rate, and the rate will most likely be higher in some future years. That means that the annual interest on the Trudeau government’s debt amounts to about $70 for every Canadian ($2,000 X 3.5%).

That means that next year, you are going to be paying $70 in taxes to the government to cover the interest on the debt incurred over the last four years. For that $70, you are not going to get anything at all. No roads, no schools, no hospitals, no police protection, nothing. It is like taking $70 from your pocket and burning it.

It gets worse. You are also going to have to pay another $70 the next year. And the next year. And the next year. And every year after that for the rest of your life. And your spouse is going to have to pay $70 a year for the rest of his or her life. And so is each one of your children. And your grandchildren, and your great-grandchildren. The debt will go on forever.

And that is assuming that the Canadian government never runs another deficit and always balances the budget every year from now on. The debt will still go on forever.

Unless, that is, we decide to pay it off. So, next year, let’s all agree to pay an extra $2,000 each to the government and pay this thing off. Don’t forget to kick in an extra $2,000 for your spouse and each of your children.

Too much? Okay, let’s pay this off a little more gradually. Let’s all pay $140 a year instead of $70 (and don’t forget to add another $140 for your spouse and $140 for each of your children). Remember this is $140 for which you will get absolutely nothing. No roads, no schools, no hospitals, no police protection. Nothing. It will all go to pay off the debt, including interest. Will that work? Sure. But it will take about 15 years. Can you afford that?

Remember, also, that every dollar the government spends on interest is a dollar that it does not have available for roads and schools and hospitals. In 2017-2018, the federal government paid $21.9 billion in interest on its accumulated debt. In 2019-2020, the government is expected to pay $26.2 billion on interest. And the amount is expected to continue to rise every year in the future unless something changes. Think about how much good the government could do with $26.2 billion if it wasn’t wasting it on interest payments. Think of the new programs that could be implemented. Think of the taxes that could be reduced or eliminated. (If it were not for interest payments, the government would be running sizeable surpluses every year.) Think of what you yourself could do with that extra money as a result of the lowered taxes.

Let Someone Else Pay

Now perhaps you are saying that you don’t make that much money, you pay very little (or even nothing) in income tax every year, so you will not really have to pay your share of the debt anyway. Let the government tax the rich or tax big companies. Let them pay for your share of the debt.

But you are forgetting about sales taxes (remember the GST?) and levies such as carbon taxes. You pay taxes on almost everything you buy. But it gets worse. There are also hidden taxes on some goods (such as gasoline). And don’t assume that the taxes that big businesses pay will have no effect on you. Companies pay payroll taxes for their employees and sales taxes and carbon taxes and import duties and various other fees and licenses. There are taxes on everything companies produce, import, or sell. How do these companies get the money to pay all those taxes? By raising the price of the goods and services they sell to you. There is at least a slice of tax embedded in everything you buy. You are going to pay. No matter how you try to avoid it, you are going to pay.

Keynesian Economics

Now, you may ask: Isn’t there some theory that says it is sometimes good for a government to run a deficit in order to stimulate the economy?

You are talking about something popularly called “Keynesian economics” (named after a 20th-century economist named John Maynard Keynes). The theory is actually quite complex, and it was not all developed by Keynes, but let’s simplify the issue.

In general, Keynesian economics suggests that a government should spend more than it brings in in taxes in bad times. This will stimulate the economy and prevent unemployment. Conversely, when times are good, the government should raise taxes, cut spending, and run a surplus in order to slow down the economy and prevent inflation. There is some merit to the theory, and it works in a general sort of way.

Something similar works for individuals. Remember that year when you lost your job? You borrowed money to pay your bills until you could get a new job. Then, when you were working again, you began to pay off the debt or even put some money into savings to help you out on the next “rainy day” when you would have some unexpected extra expenses or some reduction in your income.

It works in theory, for individuals and for governments. Except that too many governments (and, it must be said, too many individuals) never get around to the second half of the theory. They never get around to paying off their debt or saving for the future.

What Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government has done over the past four years is particularly irresponsible. It has run massive deficits (of close to $20 billion a year) at a time when the economy was doing very well and unemployment was very low. It might be remembered that the Stephen Harper government ran big deficits to counter the effects of the 2008 worldwide recession, and it worked very well for the Canadian economy. But once the recession was over, the Harper government began moving toward running small surpluses to pay off the debt it had accumulated.

In contrast, there is absolutely no economic justification for the deficits the Trudeau government is running.

It Could Get Worse

There is an even bigger danger to governments running unnecessary and irresponsible deficits. Essentially, it puts government finances in a precarious situation. It means that the government will not be able to respond appropriately when the next recession hits. If it is already running a large deficit, it will not be in a position to increase the deficit to counter the recession without facing very serious consequences. When a government’s debt becomes too great, lenders will refuse to lend any more money and/or will charge higher interest rates. At that point, the government will be forced to cut spending, reduce government grants and services, and increase taxes. This will deepen the recession and throw millions of people out of work. In essence, when a government (or an individual) gets too deeply onto debt, it goes bankrupt.

If that happens, it will very definitely affect you.

We may think it won’t or can’t happen here, but it can. It has happened recently in Greece and Spain and many other countries. Lending analysts have already begun expressing concern about the increasing levels of Canadian government debt and issuing warnings about possible interest rate increases.

So, does the Canadian government’s budget deficit matter to you?

Absolutely, it does.